The Labor of Looking: from Intention to Interpretation

This paper was originally presented at a February 2012 College Art Association panel organized by Coco Fusco, it was edited and revised in April 2013

Because I am an artist and an educator, I mostly critique in a verbal, face-to-face form, standing in front of artworks. Sometimes students want me to critique an unformed idea and I refuse because the idea will invariably shift once it takes physical form. The philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell named two types of knowledge: knowledge by description (knowing the rules of mathematics or grammar, for example) and knowledge by acquaintance (knowing how to perform the rules via lived experience). A child learns language through acquaintance, in a pragmatic and bodily way, by singing and imitating sounds and intonations, not by learning the rules of grammar and diagramming sentences. Yet we often underestimate learning via acquaintance. Making and interpreting an artwork can only happen via acquaintance with its materiality. Even the absence of physical form changes one’s experience: a moment of silence, for instance, heightens our sensory observation of the everyday. When students are stumped in front of an artwork, I ask them to merely name the physical properties of the object. A mental block is overcome when they stop trying to jump to some complete and cogent analysis. In speaking the description out loud: “it’s pink, vinyl, it’s the size of the palm of my hand…” inevitably some analysis will follow because these material characteristics always provide some cultural or personal association, some connection to another artwork or some immediate bodily response.

I start by looking at the thing in front of me to see how far I can get, before turning to the museum’s wall text or the artist’s stated intentions. While I don’t believe that the artwork can be completely autonomous, living in a pre-lingual or prehistoric vacuum, it should have an odd kind of assertiveness. Of course my knowledge and biases factor into my read, but I prefer an artwork that meets me halfway. The artwork presents the artist’s ‘implicit intentions’. Thomas McEvilley describes a hypothetical scenario of examining a painting by an unknown artist in a museum while the guard changes the wall text to correct its date from 1860 to 1960: “One’s critical awareness shifts immediately in response to one’s new sense of what the artist knew, what paintings the artist had seen and what the artist’s ‘implicit intentions’, [emphasis added] given his or her historical context, must of have been.”i In critiquing artwork, these implicit intentions (those surmised by the viewer) should remain somewhat distinct from the author’s stated intentions. Rather, these implicit intentions are posited via physical (the painting) and circumstantial (the date on the wall text) evidence, and become part of the viewer’s interpretation. In his Patterns of Intention, Michael Baxandall’s describes this process:

The intention to which I am committed to is not an actual, particular psychological state or even a historical set of mental events inside the heads of [certain artists], in light of which – If I knew them – I would interpret [their works]. Rather, it is primarily a general condition of rational human action which I posit in the course of arranging my circumstantial facts or moving about on a triangle of re-enactment.ii

To interpret is thus a kind of triangulation: the viewer, via an artwork, re-enacts the artist’s thoughts and experiences. The meaning of an artwork thus lies within the expansive and permeable consensus of many viewers’ interpretations, and is not contained by the author’s intention. Of course, there is Roland Barthes’ 1967 essay Death of the Author that shifts the locus of meaning away from the author to the reader: “a text’s unity lies not its origin but in its destination.”iii And Sol Lewitt, who in 1969, said: “the artist may not necessarily understand his own art. His perception is neither better nor worse than that of anyone else.”iv As an artist, I take these statements not as opinion, but as method, a liberating rather than a limiting one. These declarations of authorial impotence and blindness are a challenge, not surrender. Authorial blindness is inevitable, due in large part to the unconscious internalization of identity and influence. It is the paradox inherent in seeing one’s practice from the point of view of an observer, a kind of Lacanian mirror stage crisis of misrecognition, in relation to the presence of one’s own artwork. The artwork’s meaning, rather, emerges through a process of coming into physical and material being and confronting its first viewer, who is inevitably the artist. So ultimately, it is not the polemics of author and reader (that the Barthes text might suggest) that matter, but the act of interpretation which the two parties share, as Stanley Fish describes:

Whereas I once agreed with my predecessors on the need to control interpretation lest it overwhelm and obscure text, facts, authors, and intention, I now believe that interpretation is the source of texts, facts authors, and intentions. Or to put it another way, the entities what were once seen as competing for the right to constrain interpretation (text, reader, author) are now all seen to be the products of interpretation.v

Thus, in the most pragmatic sense, if the artist can interpret the work as another viewer would (in a kind of out-of-body experience, without entanglement to his or her original intention) he or she is rightly challenged. The artwork’s meaning accumulates as it confronts yet more viewers.

In her text Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag calls for an ethos of viewership as well as an ethos of authorship in relation to images of war, death, destruction and suffering. She contemplates a third space between sensationalizing and desensitization, a place where actual empathy might exist. This space is the crucial ground critics must seek when looking at all artworks: we need to validate a labor of looking, where we cultivate empathy with the artwork, and the author’s implicit intentions. It should be noted that empathy here is a learned identification, quite the opposite of ‘pity’, which is just another kind of objectification. Because as viewers, we are also constantly subject to the same unconscious internalization of identity and influence, to bias, the best we can do is to acknowledge and name our own biases out loud in an attempt to dismantle them. When teaching critical theory to students, I ask them to understand and summarize the text before they critique the author’s point of view. This process is akin to describing the physical properties of an artwork before launching into a critique. This slowing down, this labor of looking, always yields a much more nuanced, complex and thoughtful critique. In the end, I am asking readers and viewers to inhabit the author’s subject position rather than simply ‘other’ him or her. We should not mistake laziness and aggression for honesty and criticality.

One class group critique revealed to me precisely the nature of this kind of authorial misrecognition. In her BFA thesis show, the student had painted two large paintings on unstretched canvases that she had stapled to the wall. In each mostly monochromatic painting were oil painted line drawings depicting one white woman and one South Asian character. One painting depicted a South Asian bride in fully ornamented attire and jewelry touching the chin of a white woman. The white woman looked at the viewer or metaphorical cameraman with a cautious smile, while the South Asian woman looked at her with a straight-faced expression. The second painting depicted another white woman in an evening gown touching the hand of what appeared to be a South Asian rickshawallah, street vendor, or laborer in a lungi or sarong wrapped up between his legs as these laborers do. Again the white woman faced the viewer with a smiling expression of one posing for a snapshot, whereas the South Asian man also facing the viewer appeared stone faced in his expression. This painting included a drawing of the sun, with decorative lines or rays emanating forth and spilling into the scene. The decorative elements referred to Indian folk painting and henna designs painted on brides’ hands and feet, as well as 1960s psychadelic designs influenced by these forms. These elements confused two and three dimensional space and lent an air of fantasy and abstraction to the works. The two white women were also represented in two other portraits, hanging sculptural paintings suspended from the ceiling. Each woman’s portrait was decorated with glued on sequins, mirrors, and painted flowers and other decorative motifs, and adorned with hand painted texts of their first names. On the floor was a cheap Persian style rug, not part of the exhibition, brought in as a seat for the class, but affecting the experience of the show. The walls were painted a bright magenta to just above the height of the paintings.

The student started by saying that she had made the paintings out of an interest in pattern and decoration and that after four years of conceptual critiques and ant-formalist bias at Cal Arts, she had finally found the courage to do what she had wanted. When prompted to speak of the narrative of the characters represented in the work, the student stated only that the two white women were images of her friends, while the two other characters had originated from images off the internet. When asked what the contexts of these internet figures were, the student was unable to answer, and say only that she chosen them for the decorative nature of their dress conforming to her desire for lush and decorative paintings. Hearing the student’s intentions revealed crucial unconscious intentions and unintended consequences.

I had already formed a narrative of tourism around these works. These women seemed to have traveled to the Indian subcontinent on vacation, encountering the bride and the laborer, and then returning with virtual snapshots of their experiences and decorated souvenir portraits hanging from the ceiling. Even the use of mirrors on the hanging portraits referred back to South Asian decorated handicrafts and fabrics. The student responded to my interpretation, saying she hadn’t intended these paintings to be about tourism or about India. When I realized that the work was more intriguing than what she had to say about it, I did something I rarely did before this point: I asked that the student not to speak anymore until the end of the critique, when she could respond to the class, in the hopes that she might listen.

Many of the students spoke and reiterated the tourism theme. Others noted the disparate class backgrounds of the laborer and woman in an evening gown, a potential historical colonial servant/memsahib relationship. The idea of fantasy came up several times as the patterns overtaking the image spoke to surreal space, or the trippy qualities of psychadelia. A complete and convincing surreal touristic fantasy emerged as a consensus of meaning in relation to these works, mirroring the internet tourism the student had employed in her process. Some students remarked on the passive or at least stoic expressions on the faces of the South Asians in comparison to the smiling and wide-eyed expressions of the women. Students rather revealingly remarked that the white women seemed familiar, and one likened the woman in an evening gown to a David Hockney portrait of a collector recently exhibited at LACMA. The South Asian people however were less familiar to some in the audience, much more difficult to place or empathize with. Did these paintings split the identification/objectification binary of psychoanalysis along racial lines? But I was one of a handful in the room who felt that the South Asian characters were also people I had known. My identification with these figures was something I thought the author might like to hear about, since she took the view of objectifying them, though not sexually, she saw them as mannequins for decorated clothing to hang on, not accounting for the ramifications of representing them.

Was objectification of these figures inherently wrong or unacceptable? If the student had been of South Asian background would such objectification become acceptable? I don’t believe that the role of the group critique is to establish rules or off-limit subject matter for some and not for others. When the critique does so, it reaffirms the ideologue’s position and exaggerates the student/teacher hierarchy. Rather the critique should frame the terms of the debate, and allow the students to understand the distinction between a figure we identify with versus one we objectify and the ‘reversibility’ of these two types of images. For one could simultaneously read this work as mocking of the white women and their fetishization of another culture. Were the white women so clearly the protagonists? It seems the centrality of their position in the exhibition and steadiness of their gazes would say so, but I’m not so sure. At least one of their gazes seemed tentative and unsure. The woman with the bride seemed a little overwhelmed to me. Perhaps I was ‘othering’ them, just as she seemed to be ‘othering’ the South Asian figures?

In his essay on Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of the black male subject, Kobena Mercer describes the complexities of the role an author’s intention plays in a work’s read. In 1989, Mercer revises his first essay of 1986 that takes the photographs as cultural artifacts of how white people stereotype black male sexuality “at the center of colonial fantasy.”vi This former read ignores Mapplethorpe’s intentions as described in his written statements. Mercer’s second essay written three years later, by contrast, offers a more sympathetic view; in light of the politics of the religious right at the time, Mercer reverses his interpretation. He takes into account comments made by Mapplethorpe and some of his black models that offer a perspective on the author’s identity as an urban gay male artist. Mercer addresses the ‘reversibility’ of the gaze in Mapplethorpe’s work, which he says, potentially offers a critique of racial and sexual stereotypes as opposed to an affirmation of them. Mercer offers “a reconsideration of post-structuralist theories of authorship”:

Although romanticist notions of authorial creativity cannot be returned to the central role they once played in criticism and interpretation, the question of agency in cultural practices that contest the canon and its cultural dominance suggest that is really does matter who is speaking.vii

Is it not true, that Mapplethorpe’s images of black men revealed a very honest, if possibly unconscious racial fetishization, one that he had likely internalized via the culture at large? Perhaps the ambivalence that Mercer’s double essay presents is the very ambivalence of Mapplethorpe himself, the paradox of both objectifying and identifying with these black subjects?

At the heart of making art and looking at it is the very process of bridging the impossible gap between one’s own internal musings and the experience of the ‘other’ – the viewer, and the artwork is an intermediary, an offering, a very physical emissary of sorts, which speaks of our exile from one another, or sometimes of our complete sameness. While authorial intention and viewer’s interpretation often overlap and effect one another, as they did in Mercer’s re-reading of Mapplethorpe’s work, they are never one and the same, nor should they be. Again, what triangulates between them is the art object itself. Students often lament that viewer’s did not ‘get it’, did not interpret their work as they had intended them to. And some teachers preach that a work that does not reflect the student’s stated intentions has failed. But without this distinction between intention and interpretation, the artistic process would become one of mere execution, and we would learn nothing about our shared history, community, and humanity. Indeed, the notion of shared institutional and cultural community is central to this example of the group critique and is implicit in most forms of art criticism today, as Stanley Fish has aptly noted, while the drawback of institutional communities is that of limitation and bias, they can also mitigate empty pluralism (anything goes), and solipsism: “The condition required for someone to be a solipsist or a relativist, the condition of being independent of institutional assumption and free to originate one’s own purpose and goals, could never be realized, and therefore there is no point in trying to guard against it.”viii

While in graduate school, I made a painting of a hand painted houndstooth pattern, after seeing the Agnes Martins at the Guggenheim museum. I considered the project a kind of Duchampian critique of modernism, a fusion of the high and low. However, given the slow and laborious nature of my process, the final object took on a degree of earnestness: a quiet homage to Martin, rather than a critique. Further, while my use of the houndstooth originated from my interest in the decorative and the domestic; its modular quality ended up speaking much more to the digital image. Only later, did I read about the historical connection of weaving to early computing technology; the early punch card (Jacquard) looms had laid the groundwork for the early punch card computers. The cheap piece of printed houndstooth cloth that inspired the painting had its own historical memory, and by using it in my artwork I unwittingly stumbled upon new content. My work to the present day refers to the experience of the digitized screen. When I made the Houndstooth painting, I did not ‘intend’ to speak to digital technology, but accidental discoveries in the studio lead to historical and material epiphanies. Similarly, my student’s revelation that the pattern in her work addressed issues of tourism and exoticism could provide new pursuits in her studio.

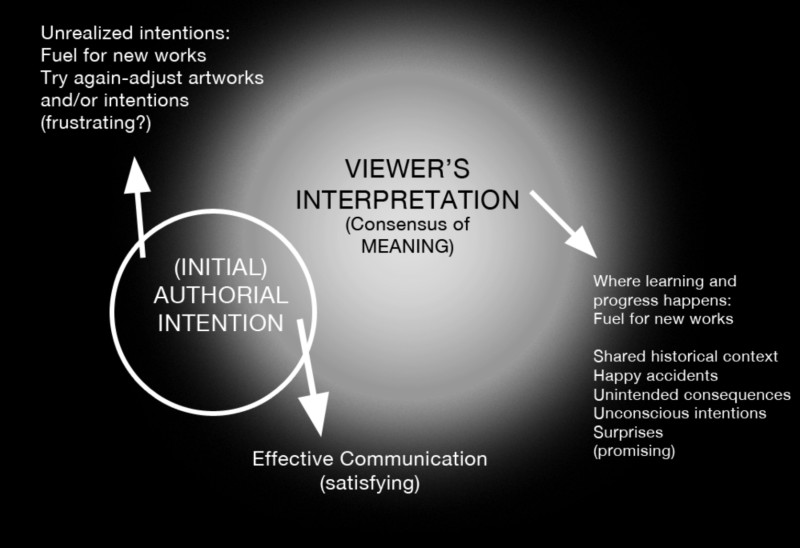

A venn diagram, originating as a scrawled doodle during a visit with a student, might more simply summarize my point:

Our initial authorial intention can feel fixed and ideal: therefore a closed circle illustrates it. Viewer’s interpretations are multiple, changing and fluid. However, they are not completely erratic, and meaning is not completely contingent: the accumulation of interpretations in a given moment in time makes up kind of expansive and permeable consensus. I thus imagine these interpretations unlike a fixed circle, but as a dense glowing sphere of light, moving in many directions. These interpretations will inevitably be mis-registered with our intentions, creating a ‘surplus’ of meaning. In this surplus are all the unintended consequences of our production: happy accidents, unconscious intentions, and material realties with their own historical memory. If the intention and the read of the work were completely congruent, surprise and subsequent growth in art production would be lost. Artists are constantly discovering and revising their intentions as well as the work itself. And what of our unrealized intentions? While they may be frustrated, they are not failures, rather moments of self-adjustment or fuel for future artworks. Ultimately, this approach to critique can be more truly non hierarchical and non combative. That authorial intention does not exist in some kind of domineering or violent struggle with its viewer’s interpretation allows us to talk about their relationship with calm, clarity and effectiveness. Energies can be focused on making more work, experiencing and understanding work, rather than pointless ego struggles.

Finally, we live in a culture that privileges ‘knowledge by description’ and technology can emphasize this privilege. To know something, all you have to do is google it in a completely disembodied way and you get much description. The seamlessness and perfection of the screen never reveal their vast technological and cultural mechanisms. But do we really know things? Because you can quote something, because you can read about and describe it, do you really know that thing? Making art, and the process of looking at it, are acts of acquaintance. Together they make up, what I call the ‘Labor of Looking’, which is my shorthand for describing a heighted material observation and experiencing that challenges accepted ways of being and knowing. A respect for material processes and accidental discoveries is a reminder to balance untested strategies and hardened biases with physical conditions on the ground.

i Thomas McEvilley, “Heads It’s Form, Tails It’s Not Content,”Artforum, 21, no. 3 (November 1982), 52.

ii Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 41.

iii Roland Barthes, “Death of the Author,” in Image, Music, Text, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 148.

iv Sol Lewitt, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” in Art in Theory 1900-1990, Ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, (Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 838.

v Stanley Fish, Is There a Text for This Class, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980), 16-17.

vi Kobena Mercer, “Reading Racial Fetishism: The Photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe,” in Welcome to the Jungle, (New York: Routledge, 1994), 177.

vii Mercer, 194.

viii Fish, 321.